Ayse Papatya Bucak

Documented

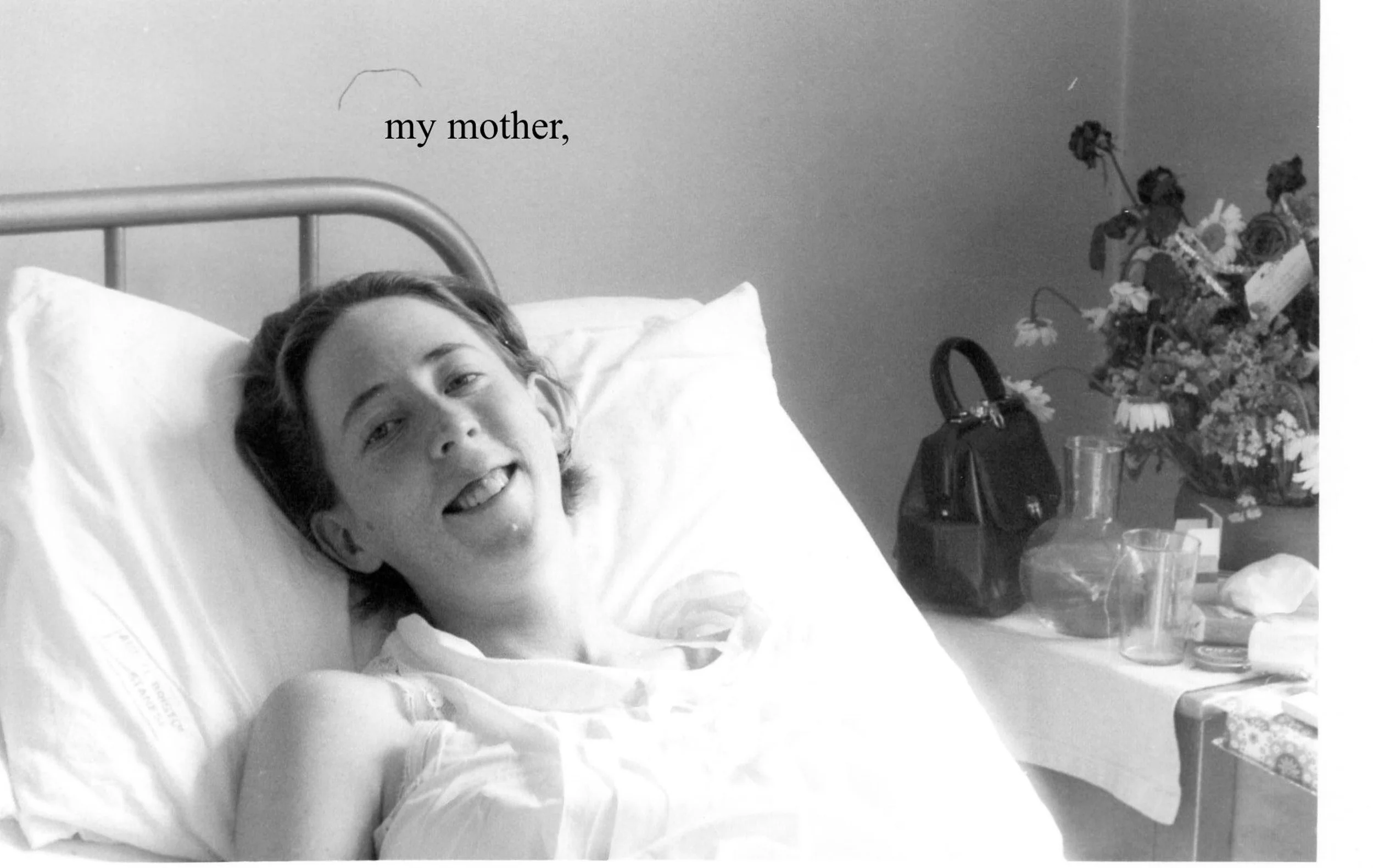

It was the summer of 1964 when my mother, an American, met my father, a Turk, in a dancing class at International House in Philadelphia, where my father was living while attending the Wharton School. Which he later dropped out of.

“You couldn’t resist me,” my father says.

“You were late and you had to have everything explained to you all over again, and I didn’t approve of your short sleeves,” my mother says.

Still, I guess she couldn’t resist him, because here we all are. My father, my mother, my brother, and me.

It was the summer of 1966 when my mother left America to be with my father, after she graduated college and he dropped out of Wharton. But they couldn’t legally be together until after my father had finished his military service. So she moved to Turkey to be with my father even though they would not be able to marry for two years, nor live together for one. In other words, she moved to Turkey to be with my father even though she couldn’t be.

When my mother wrote letters to my father, away for his military service, he insisted she write in Turkish. Had she written in English that might have called attention to the fact that he was in a relationship with a foreigner, which wasn’t allowed. He, too, wrote his letters in Turkish so as not to call attention to them. For a part of this time my father was translator for the Turkish Chief of Staff in Ankara. My father’s English was excellent, but he could only write to my mother in the few words of Turkish that she could understand. As a result, there was little they could say to each other in these letters. I imagine for each of them it was like getting love letters written by a child.

Once during this time my father was woken in the night to translate an urgent transmission from the Americans.

It said: Gypsy caravan on the NATO route.

My father went back to sleep and the “gypsies” were removed, let us hope gently, from the NATO route.

Because my father had broken the scoring record on his English exam, he was also given a “discreet” assignment to translate a Christmas card sent to the Turkish Chief of Staff by the wife of some American general, which she had signed “love.” The card was a United Nations card that said Merry Christmas and Happy New Year in English, German, French, Spanish, etc. My father translated this list of Merry Christmases and Happy New Years into Turkish only once, but his translation came back with a note—where is all the rest? So my father wrote “Merry Christmas and Happy New Year” in Turkish over and over and over again.

Perhaps my father ought to have translated the “love” of the American general’s wife to the more traditional Turkish closing, “I kiss your eyes,” but he didn’t. He wrote love.

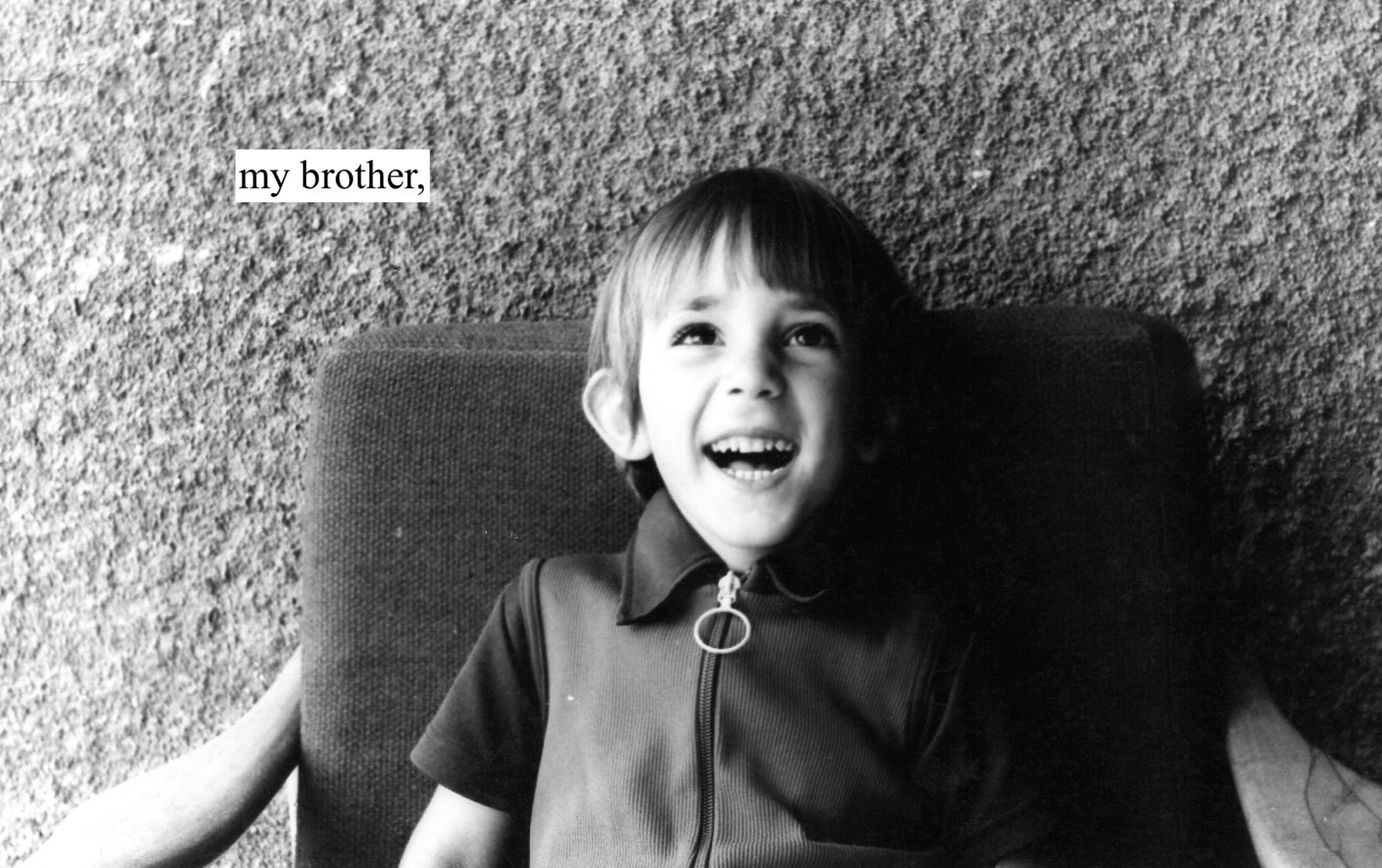

Eventually my parents were able to marry. Eventually they had a child, my brother. Then there was me. Born into a world I can’t remember.

I think I remember standing on our apartment balcony and looking down on a pair of dancing bears. I think my mother threw a coin and a Romani caught it.

I would not, at the time, have known to say Romani.

I think I remember seeing a huge snake in a park and men chasing after it with sticks.

In my memory, I see this from the snake’s perspective.

Once I nearly fell into the Bosporus when my father made me carry two heavy suitcases while disembarking from a ferry. The “ramp” was two boards laid from dock to boat, and as I stepped onto them, one foot on each board, the boat shifted in the waves so that the boards, and my feet, spread apart.

I launched myself to shore by thrusting the two heavy suitcases toward the dock so that their weight pulled me forward, straight into my father’s back.

“So really the suitcases saved you,” my father says whenever I complain about what happened.

But that was when I was a tourist—back again—not in the time that I have forgotten.

When I was four, I agreed to move to America because I was promised a Barbie doll. “You were counting on Barbies flowing in,” my mother says. My brother, who was six, agreed to move to America because he’d heard rumors of Halloween. I remember being given Coca-Cola on the plane because my tummy felt funny. My mother remembers a Turkish family whose baby had a terrible rash. My father served as their impromptu translator. Later my brother and I had strange rashes on our scalps. “You let that baby give me a rash,” I screech at my mother when she tells me this story. I am joking. Mostly.

I am embarrassed to admit that even now some part of me thinks of that sick baby as Turkish, and my healthy toddler self, headed into the future, as American.

Before my brother and I were born, when my parents would go to the movies, my father would make my mother sit on the aisle so “some strange man” couldn’t sit next to her. “Who knows what you would have done with your legs,” he said to her later. Once a Turkish judge had to gesture across a courtroom to get my mother to uncross her legs.

Sometimes when my mother and father were at the movies, the power would go out and they’d descend from the dark balcony by following people holding up the tiny flames of cigarette lighters. The power would go out at the grocery story, the dentist, restaurants, everywhere. “I don’t know what kind of nuts used the elevator,” my mother says.

The water would go out when you were in the middle of washing your hair. It would come back five or six days later.

My mother’s apartment had roaches, which “would leave their insides smashed on the floor and walk away.” “After you smashed it and smashed it,” my mother says, “its insides would stay put and it would walk away.”

My mother says she cried all of her tears her first year in Turkey, but she also says she never wanted to leave.

When my father decided to go to the United States the first time, to go to Wharton, where he would eventually meet my mother, and eventually drop out, he left behind a job offer to teach at Middle East Technical University. The university had already put his name plate on his office door, and after he was gone, my father’s mother, my grandmother, went to visit his nameplate and cry. That is the story I’ve been told anyway.

She didn’t know he would come back again. And leave again. And come back again. And leave again.

When we still lived in Turkey, my grandmother would buy clothes for my brother, and my father would say, “What about your granddaughter?” So my grandmother would buy some clothes for me and more clothes for my brother. “It never evened out,” my father said.

This is a picture of my grandmother holding my brother.

This is a picture of my grandmother holding me.

My grandmother’s father was an Islamic judge who fell out of favor during the late stages of the Ottoman Empire. As punishment, he was sent to some remote area where he and his wife caught typhus and died. My grandmother and her sisters were all orphaned.

As a young woman, my grandmother was friends with Sabahattin Ali, a Turkish writer who was often jailed for being a Communist. Later he was killed for it.

Once Sabahattin Ali, in response to a letter from my grandmother, said, “You have a clear and delicious writing style.” He also sent her a poem about the “saddest part of his sadness”. It was titled “Melancholy,” and in the 1970s, long after Sabahattin Ali was killed, it was turned into a Turkish pop song.

Sabahattin Ali’s letters to my grandmother, which my grandmother hid for years at a friend’s house, were eventually published in a book that became a modest success in Turkey. In one letter, he tells her “it is an insult to love to think of it as an occasional need like opera glasses.”

Because I don’t speak Turkish and my grandmother didn’t speak English, we had very few and very short conversations. Now I can only read those of her letters that my father translated for me, which are not many. Yet I can’t help but feel that if my grandmother and I could have talked about books, we would have liked each other a great deal.

When we lived in Turkey, my mother, the American, wanted my brother and me to learn Turkish, and my father, the Turk, wanted us to learn English, so my mother spoke to us in Turkish and my father spoke to us in English. So my brother and I spoke toddler Turkish with an American accent, and toddler English with a Turkish accent.

My father’s father, my grandfather, died while my father was translator for the Turkish Chief of Staff in Ankara. My father was given leave and “he appeared suddenly” according to my mother. “I made him sandwiches. He ate like a pig.” That was 1967. The same year my father broke his foot jumping through a window to impress my mother and so got forty-five days leave from his compulsory military service.

In 1974, when I was three years old, my father was called back into the military because of fighting in Cyprus. He was sent to base to “hold down the fort.”

As he was the ranking officer, each morning he’d tell the men to find a shady spot to do calisthenics, and at night he’d turn out the lights and tell them stories.

In the meanwhile, in Istanbul, my mother, left at home without any money and with two toddlers and an American visitor who was a co-worker of her sister’s boyfriend who stayed a week and “paid only with a watermelon,” went under the bed every time military jets buzzed the Bosporus. I assume my brother and I went under the bed with her, but we don’t remember, and neither does she. “Obviously I took care of you,” she says, when I complain about this.

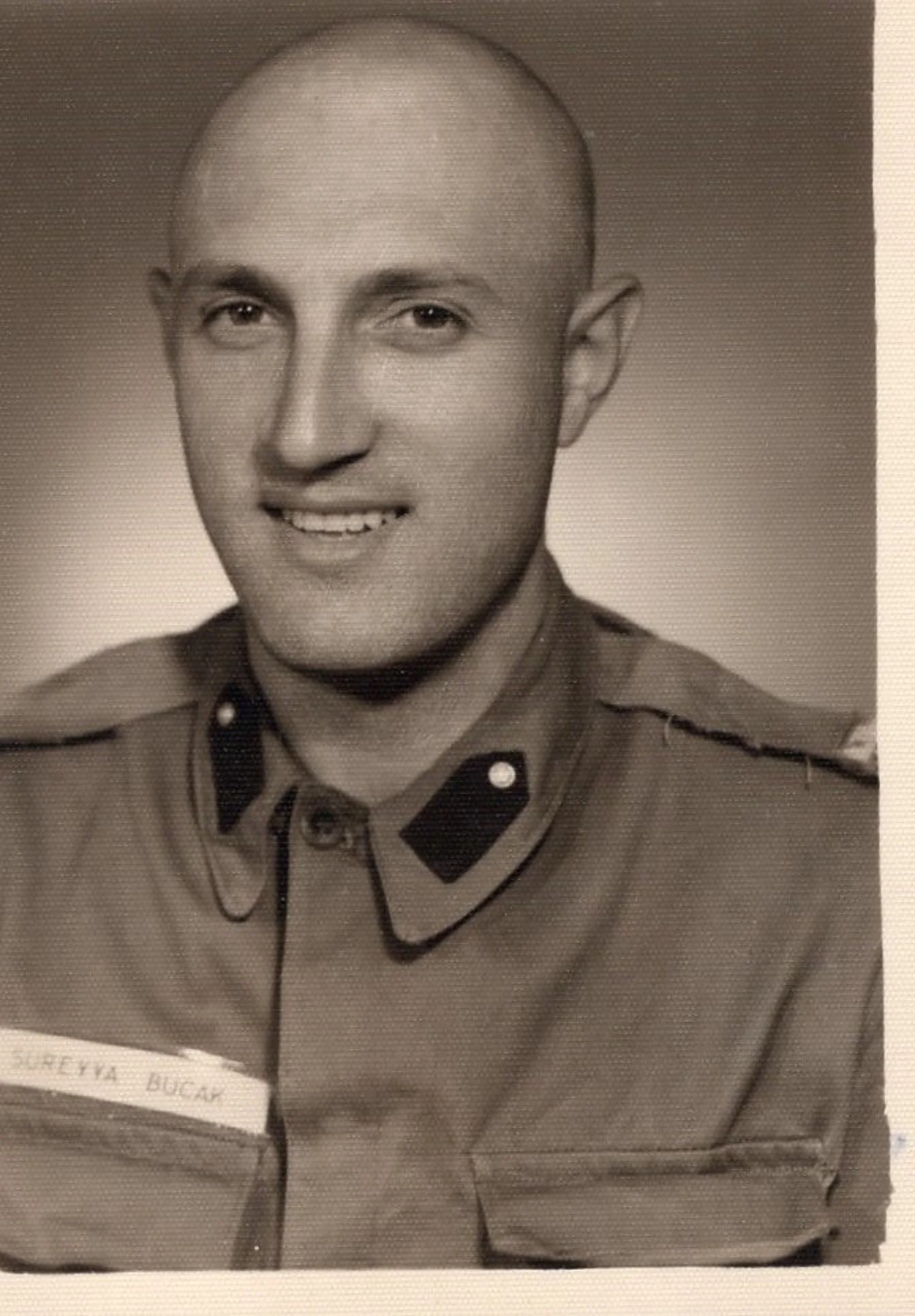

All I remember is that my father came back with a shaved head and a gun.

“There was no gun!” my mother insists. I insist there was, but nobody considers me a reliable witness.

When I asked my father, he couldn’t recall.

I sometimes think of

as the only citizens of a very small country that existed for only a very short time.

Later, when I was in my twenties, my father took me to Turkey three times. Like three wishes. In my grandmother’s apartment, I sat in the rocking chair where my mother nursed me as a baby. In my grandmother’s living room, I found the copy of Little Men to match the Little Women and Jo’s Boys in my parents’ house. How can those three trips be anything but magic, but myth? While we traveled, my father kept forgetting that I didn’t speak Turkish, and I had to keep asking, what did you say, what did you say? He befriended so many bus drivers and hotel clerks he claimed he could run for office. He incited our cab drivers into heated conversations during which they would nearly drive off the road. One time, the only word I recognized was Vietnam, Vietnam. How can those three trips be anything but a beginning, middle and end?

Look at my family before I was born. Look at my father! Look at my mother.

I see myself there so easily, even though I was not.

I love to remember things I never knew.

Before he died, my father joined the tribe of the forgetting. An unwashed, irritable, difficult tribe, often found in its underwear. “The short sleeves should have been a warning,” my mother says.

Before he died my father said, of living in America, “I’m sorry I brought us all here.”

I regret my reply, which was to screech, “Are you crazy?”

When I was three, my mother used to hang out the window of our apartment and watch me walk by myself to the ice cream shop at the end of our street. I am a coward and my mother is a coward so it remains shocking to both of us that I did this and she let me. The man behind the counter would sit on a huge stool—the tallest stool you can imagine—and he wouldn’t see me until I said, “Dondurma isti urum.” Then he would peer down at me.

I only ever retained the Turkish of a child—ice cream, monkey, yes, no, please, thank you, I want. One of the Turkish phrases I know now is “I’m dying.” Also, “What day is it?” And, “When is she leaving?” That is the language my father spoke before he died.

Before he died, my mother began doing push-ups so that if the time came she’d be able to lift my father onto the toilet. She says she was in training like Owen Meany.

My family has always been drawn to books.

Once when my mother and father were fighting my father said to my mother, “Why did you go to Turkey then?”

My father wanted to go to Turkey one last time. He said, “the ground is calling.” My mother wanted to go, too; but they didn’t. They couldn’t. They got old here, and here they will stay.

“Your mother is like Sisyphus and Atlas combined,” my father said. “She is pushing the world up a hill—and I am perched like Buddha on top.”

My father was always good with a simile.

My mother believes in djinn. She thinks one curls up at the bottom of her bed and gives her nightmares. “I told your father to kick him off,” she says, “but he couldn’t do it.” He wasn’t strong enough.

He was never really strong enough. But then love is not a pair of opera glasses meant for occasional use.

After my father died, my mother had a nightmare in which he was calling from an airport but every time she asked, “Where are you?” she could not hear his answer.

You would think this was an obvious metaphor for death but in truth my mother has always had nightmares in which somebody somewhere is lost. My mother thinks it is her job to keep track of us all.

I, too, think that is my job.

Ayşe Papatya Bucak is the author of The Trojan War Museum and Other Stories. Her writing has been published in a variety of journals including One Story, Bomb, the Iowa Review, Guernica, and Witness. Her stories have also been selected for the O.Henry and Pushcart Prize anthologies. She is Associate Professor of English at Florida Atlantic University.