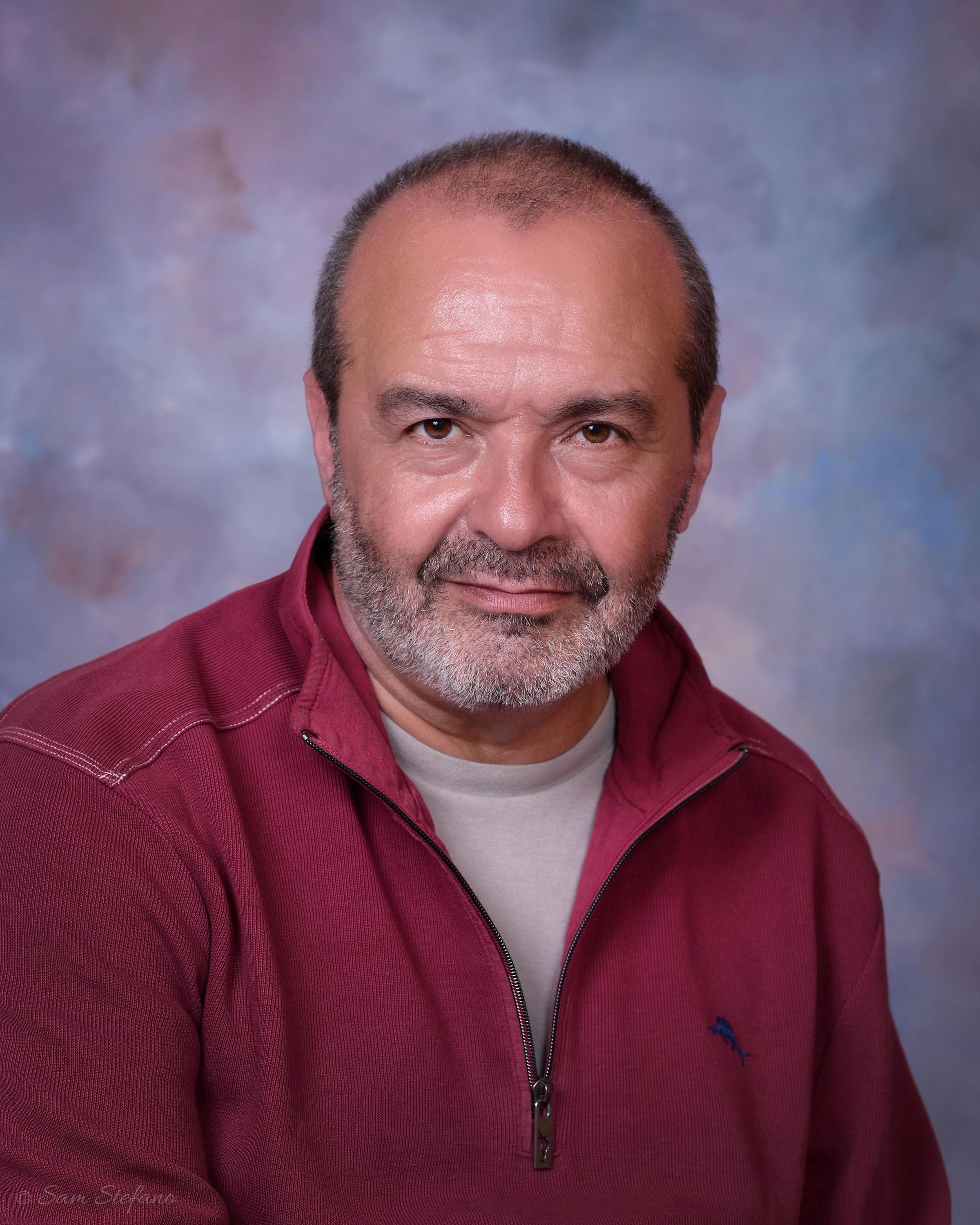

Victor Shenderovich

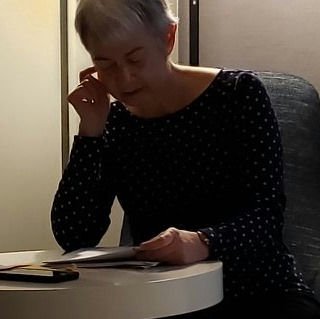

TRANS. BY Marian Schwartz

Wind Over the Parade Ground

Dedicated to the Order of Lenin Transbaikal Military District

At this point, it’s anybody’s guess who first noticed the yellow aspen leaves falling thick and fast at the marchers’ feet. The leaves didn’t stop them from marching, but this particular pastorale is not about training drills.

The regimental commander gave an order, and the second company, armed with brooms, went forth to do battle with autumn.

That night, on his way to check the sentries, the officer of the day took a deep lungful of the slightly bitter smell of rotting leaves. The dark parade ground reflected the sky. The disarray had been eliminated.

In the morning, though, on their way to regimental muster, the battalions were met by piles of yellow anarchists shuffling across the asphalt. The wind swooped down, and by muster’s end the leaf-plastered officers, still trying to catch snatches of what the commander was saying, were holding on to their caps two-handed. In the rumble and rustle, the commander silently sliced the air with his palm, so that the staff caught the general sense of what he’d said, if not the content.

As the regiment cooled their heels on the parade ground, warrant officer Trach, stamping at the back of his platoon, said to warrant officer Zelenko: “Some weather. . . . Guess we should go warm up, Kolyan, right?”—and he elbowed him in the side. “Nothing to warm up with,” Kolyan replied gloomily, and he turned his back to the wind. They talked, and the wind blew and blew, and the leaves gusted past the company columns in fits and starts.

After muster, the seventh company remained on the parade ground to march back and forth in formation, as is the custom here. The regiment was thin on the ground, and the sounds coming from the firing range were more muffled than usual.

Two hours passed. The wind howled, flaying the trees, but the seventh kept marching, getting bogged down in leaves as if they were snow. At the end of the third hour, on the command “Right wheel!” Sergeant Vedenyapin fell out of formation. Without a word, he sat down on the parade ground, removed his boots, stood up, and with a melancholy cry lofted both boots in the air. The boots flew off, never to return. Vedenyapin took not a step from the parade ground—and was lost forever in the fallen leaves.

When leaves began poking into regimental headquarters, which were already solidly blocked by them as it was, the officer of the day decided to send the orderly for papa-commander.

Subsequently, this orderly tried many times to explain to the military police how he could have gotten lost for half a day between the three staff buildings, but he never did convince anyone. The orderly lost his escort on his way to the guardhouse, and buried over his boots in leaves, stood in the middle of the garrison for a long time like a monument to autumn.

Without waiting for papa-commander, the orderly, now in a sweat, reported on the cataclysm to the division, which sent down orders:

• find the commander

• cease all drills

• return the company to barracks

• get rid of the leaves.

Everything was done to a T. The commander was found in his own quarters sitting with a compass over the district maps; the seventh company was dug out practically without loss; the jammed-in leaves were trucked out to the hills and buried there in a huge pit, never to be seen again.

The division commander arrived at the regiment before evening muster. He personally checked that the parade ground was clear, gave the necessary instructions concerning the restoration of military order—and split.

But the wind kept on howling because no instructions had come down whatsoever with regard to the wind.

The disaster came two hours later, when a general arrived. The stars on his shoulders were so big that the sentry fainted dead away. Whether the general was from district headquarters or Moscow itself, no one dared ask, and he himself did not say. Shuffling through leaves, the general stepped onto the parade ground, swiveled his head on his short red neck, asked why the parade ground was such a holy mess, called the staff a short and insulting name, turned on his heel, and rode off.

Watching the general’s fat car go with a baleful eye, the regimental commander carefully looked at his feet, then squinted at the sky, and in its already dim light, saw leaves falling to the parade ground, dancing in the airstreams.

He lumbered up the stairs to his office, sat down at his desk, removed his cap, and called in the battalion commanders. Messengers were sent running to the companies, ramming their shoulders into the wind, and the sergeants got busy getting their departments in order.

An hour later the regiments came to blows with autumn, battalion by battalion. Leaves that refused to fall were ripped off by hand; what was left after that was snapped in two and sawn up. Ritual bonfires sent smoke into the sky over the regiment. By retreat, instead of trees, neat white stumps ringed the parade ground perimeter in twos.

An end had been put to the anarchy. Everyone dispersed. The unit’s new orderly smoked in front of the deserted, swept asphalt field for a long time, as if still expecting some kind of trick. The lights went out in the barracks, and the last unexterminated leaf, oblivious to it all, flew up and circled over the black surface of the regimental parade ground.

At six in the morning, the young cornetist from the music platoon blew reveille and then, sticking his hands under his arms, ran to the clubhouse to warm up.

As snow fell on the parade ground.

Victor Shenderovich is an award-winning writer, playwright, and journalist who became famous in the West for “Puppets,” a cult satirical program that ran on NTV in the 1990s and that won the Tefi, Russia’s top television prize, twice (1996, 2000). He was a finalist for the first Boris Nemtsov Fund Prize (for courage) and won the Moscow Helsinki Group Prize. Shenderovich’s prose and plays have been translated into English, German, French, Persian, Ukrainian, Estonian, Finnish, and Polish.

Marian Schwartz translates Russian classic and contemporary fiction, history, biography, criticism, and fine art. She is the principal English translator of the works of Nina Berberova and has retranslated half a dozen Russian classics, including Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. Forthcoming in Fall 2016 is her translation of Andrei Gelasimov’s Into the Thickening Fog. She is a Past President of the American Literary Translators Association.