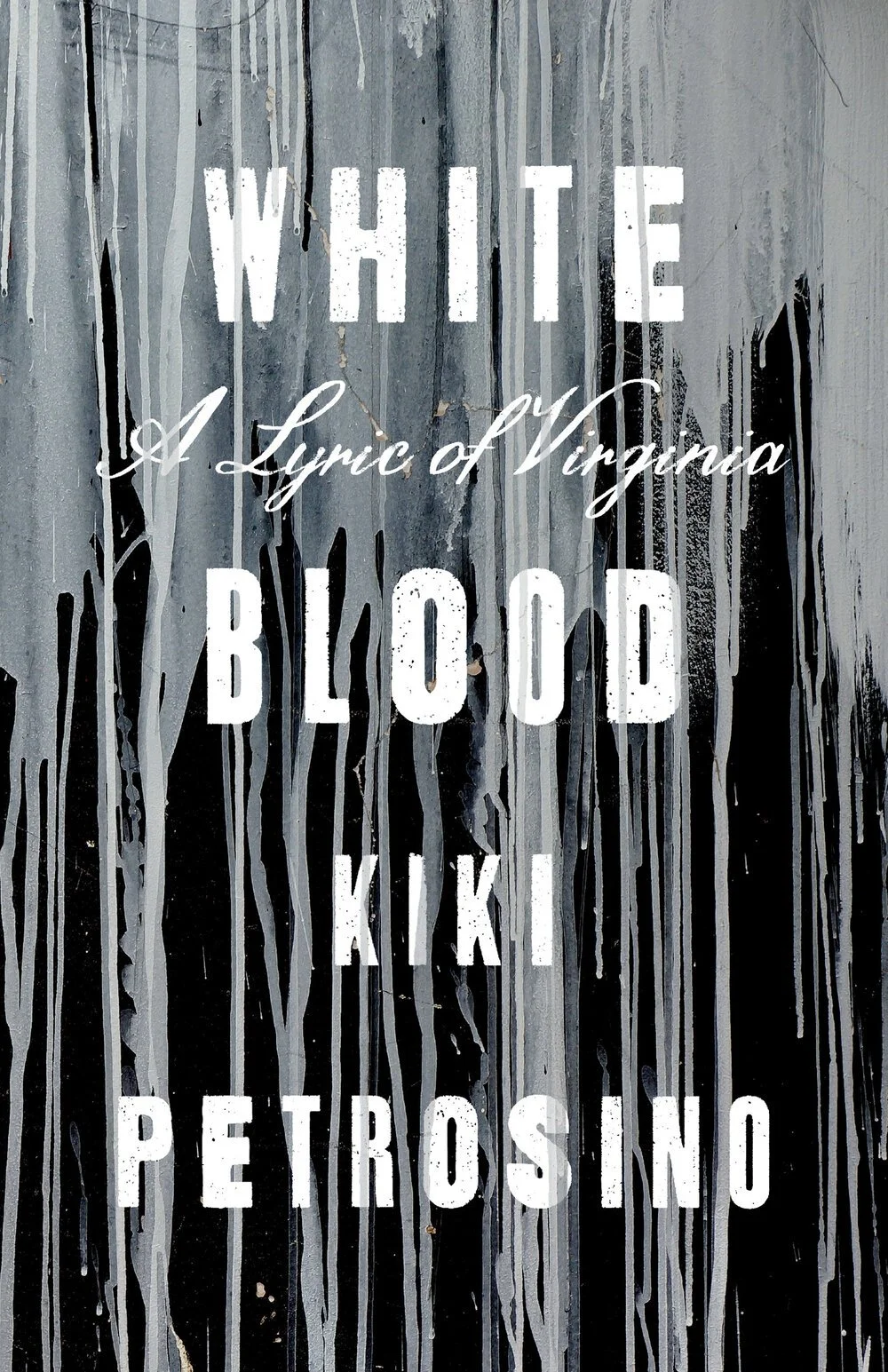

White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia

Kiki Petrosino

Reviewed by Rome Morgan

In Kiki Petrosino’s fourth poetry collection, White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia, national, family, and individual histories combine to create a multi-threaded examination of the legacies of slavery in the United States. As in her previous book, Witch Wife, Petrosino showcases her mastery of form. Her erasure poems from genealogical test results draw attention to how much is missing from these sterile summaries of ancestry. A crown of sonnets explores the speaker’s own troubled personal history of her intellectual roots. In these poignant poems, the youthful speaker is a “scholarship girl” whose confidence is slowly undermined by the hostile environment she finds herself in—“To think! Of those white kids / whose turn (some said) I took.”—as well as a great personal loss.

In the section “Albemarle,” Petrosino focuses on national narratives—the legacy of Jefferson. In “Monticello House Tour,” the speaker opens with “What they never say is: Mr Jefferson’s still / building […] After death, it’s so easy / to work. No one sees him go out / from the Residence, his gloves full / of quiet mortar.” In “Albemarle,” Petrosino considers that what Jefferson planted in the founding of the United States hasn’t only passively remained, but actively grown with the nation, his presence embodied in his legacy. In this manner, all Americans live in Monticello, within the structures of systemic racism that Jefferson helped create and reinforce even today. In this section, refrain forms powerfully communicate both the speaker’s ruminations as well as the cyclical nature of trauma that characterizes the Black experience. And in the section, “Louisa,” Petrosino situates herself within this national legacy, imagining her own African-American ancestors’ lives through archival documents of the region.

In a national history written principally by White men, missing Black and Indigenous perspectives leave gaps that may be interpreted and imagined but rarely filled. But that does not mean they can be forgotten or ignored. Instead, the missing pieces intertwine with modern life and become urgent. The collection is a keen undertaking both of that mission and of the book's epigraph, a line from a poem by Lucille Clifton: “pay attention to / what sits inside yourself / and watches you.”